Five introverts hop on a bus: my first brush with mob programming

Leaving our splendid isolation and teaming up to work interactively may give us a boost as programmers. Silver bullet or not, mob programming is an experience I strongly recommend trying at least once.

The Saturday before last was the year’s first bright and sunny day here in Berlin, so I decided to spend it in front of a screen, participating in my first-ever mob programming retreat.[1] Huge thanks to the hosts, Dimitry Polivaev[2] and Harald Reingruber[3] for dedicating a full day of their own life to this event!

If you’re like I was before the retreat, you must now be wondering: what is mob programming? Dimitry has created and shared a great slide deck[4] explaining it, along with the structure of the retreat. The images and tables below are from this presentation.

What is mob programming?

Mob programming is a form of collaborative software development where a group of 4 or 5 people work together, creating software with test-driven development and refactoring. In this one-day retreat, the teams explored changing constraints around collaboration over the course of four sessions.

The group works on a single computer at a time, with only one person typing; the others are all viewing the typist’s shared screen.

There are three roles in the group:

- The driver is the person who does the typing. I keep getting confused by the names, so I personally ended up calling this role the typist. They only type whatever they are told by the navigator.

- The navigator tells the driver what to type.

- Everyone else is a mobber.

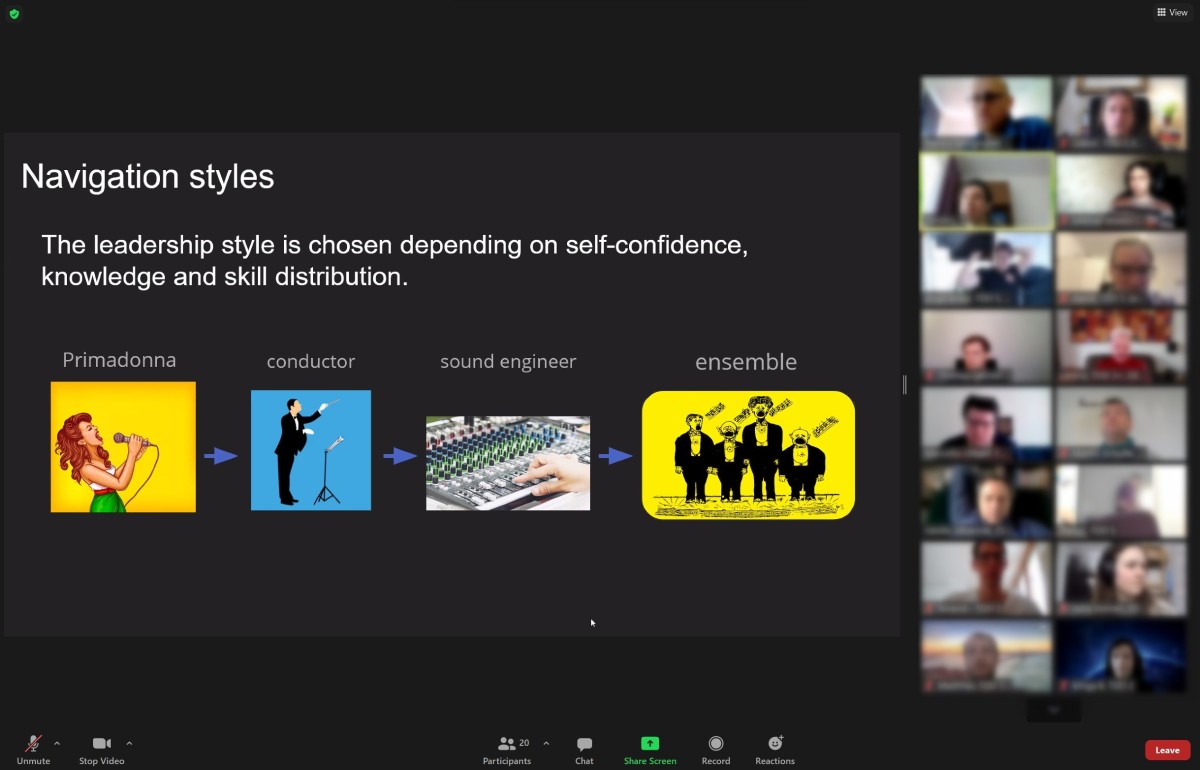

Exactly what each role does depends on the mobbing style. Because Dimitry’s slides explain this so well, I will just use them and breeze over the four styles below. But first, a few more things to explain.

- The roles are rotated on a tight schedule, every 4 minutes. This is driven by an online collaborative timer[5] that provides the rhythm and tracks the rotation of the roles.

- In the online retreat, each group had their own Zoom breakout room, and whoever was the driver shared their screen.

- We used cyber-dojo[6] for real-time collaborative coding in the browser.

- After each full cycle through the team, we used one round as a mini-retrospective. In this 4-minute round the typist wrote notes into a markdown file instead of writing a test or code.

- Two full rotations made up a session (about 45 minutes). The next session was then dedicated to a different mobbing style. Each session (2 in the morning, 2 in the afternoon) was sandwiched between time spent in the main Zoom call. These were used by Dimitry to explain what’s going to happen next, and provided room to exchange impressions, clarify things etc.

The retreat had over 20 participants (4 groups), which all independently worked on the same toy exercise, the elevator kata.[7] The audience was very heterogenous, so each group started out by choosing a programming language to work in.

The four mobbing styles

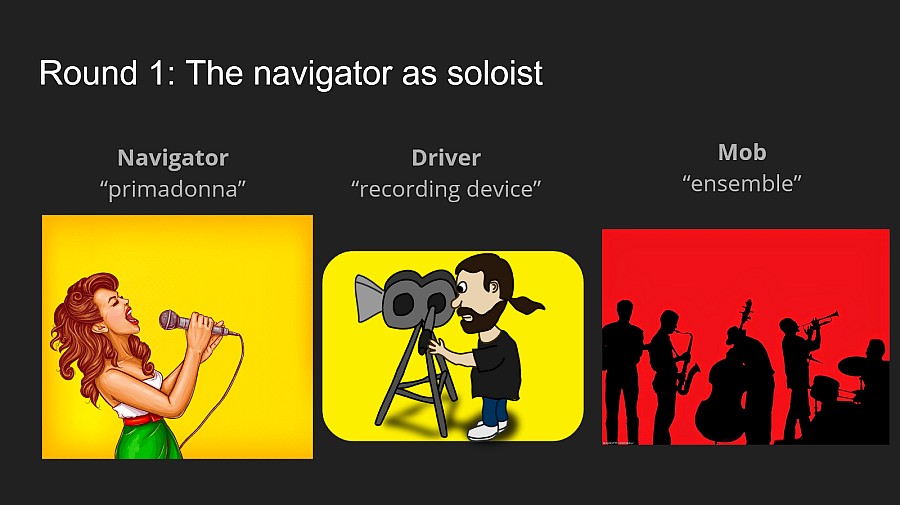

Style 1: Navigator as a soloist: leads strong

| PRACTICE | DO | DON'T | |

| Navigator Commander |

Lead, find solutions, speak to the group, communicate goals (what to achieve) and reasons (why that), give instructions to DRIVER (what to implement) at the level they are able to execute (“intention - location - details”), ask for help, listen |

Tell DRIVER what to do based on your choices. You are the decider. Whenever you need, ask for suggestions from the MOB. |

|

| Driver | Listen to the NAVIGATOR, ask for clarification or technical help |

Follow NAVIGATOR instructions Ask NAVIGATOR questions |

Type anything before being told by the NAVIGATOR Argue. The navigator decides. |

| Mob | Listen, be patient, respond to NAVIGATOR, find solutions |

Allow the navigator’s vision to play out. Create a space for learning. This may prove difficult |

Ask NAVIGATOR questions or offer suggestions before the NAVIGATOR request |

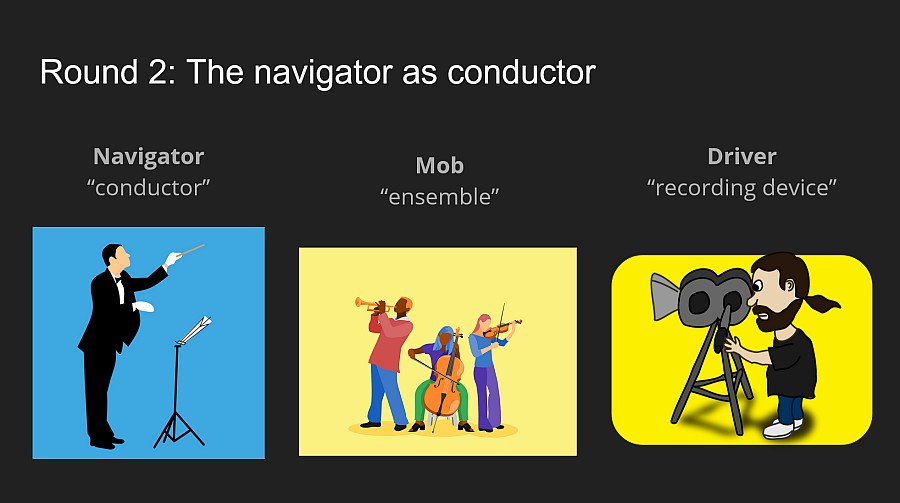

Style 2: Navigator as a conductor: moderates and decides

| PRACTICE | DO | DON'T | |

| Mob | Offer suggestions, ask questions, listen |

When intending to speak let the navigator know and wait for the moment when the floor is given to you |

No one may interrupt another |

| Navigator Chair |

Moderate the MOB, create safe environment, ask open questions, encourage everybody to contribute, make final decisions, give instructions to the DRIVER |

Give word to the members of the MOB Listen to the MOB before doing the next step Ask open questions to help the MOB (what, how, etc), Tell DRIVER what to do based on ideas coming from the MOB |

Tell DRIVER what to do based on own ideas not coming from the MOB Ask closed questions (A or B, YES or NO etc) |

| Driver | Offer suggestions like a mobber, listen, follow NAVIGATOR instructions, ask for clarification or technical help |

Always raise hands and wait for permission before you talk Follow NAVIGATOR instructions |

Type anything before being told by the NAVIGATOR |

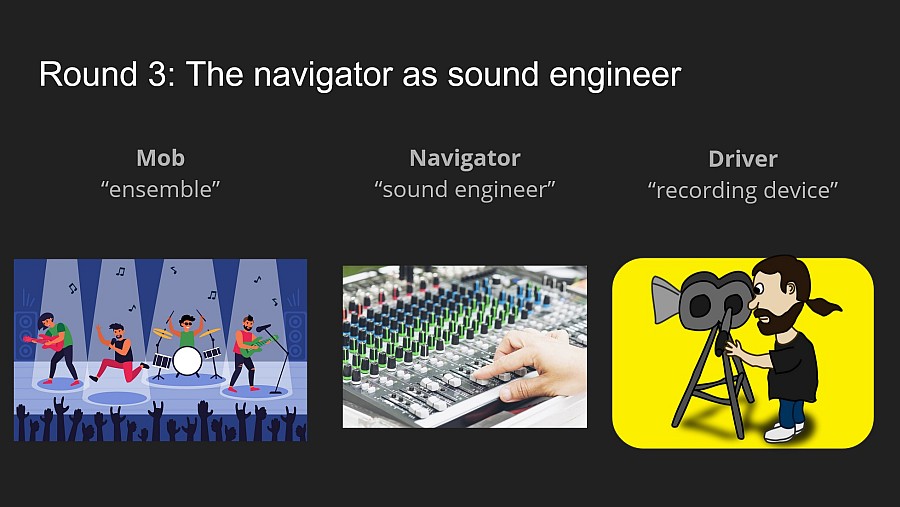

Style 3: Navigator as a sound engineer: listens and decides

| PRACTICE | DO | DON'T | |

| Mob |

Elaborate goals and implementation details without a moderator |

Make suggestions, express support or disagreement or ask questions any time |

Talk over one another |

| Navigator Arbitrator |

Listen to the MOB, make and explain decisions, give instructions to the DRIVER |

Always wait for the MOB suggestions before doing the next step Tell DRIVER what to do based on ideas discussed with the MOB |

Tell DRIVER what to do based on ideas before they have been discussed by the MOB |

| Driver | Listen to the NAVIGATOR, ask for clarification or technical help |

Ask NAVIGATOR questions |

Offer ideas Participate in the discussions Type anything before being told by the NAVIGATOR |

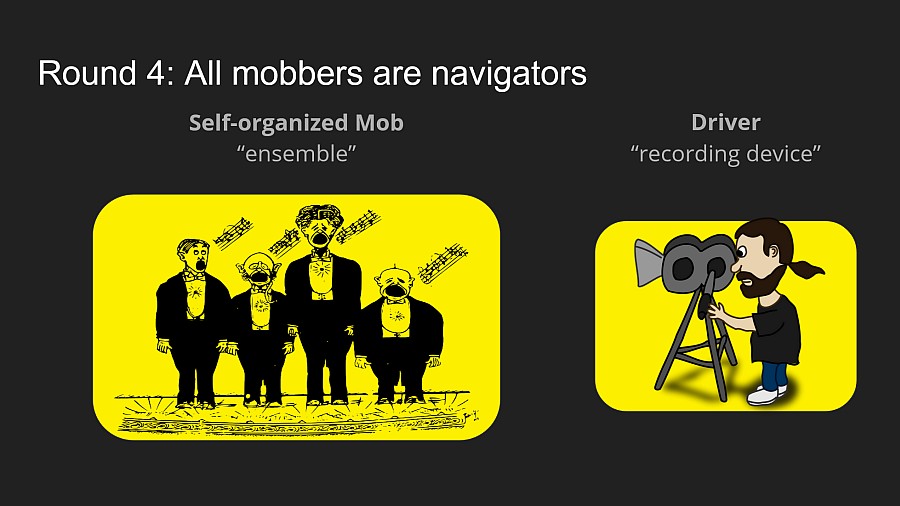

Style 4: Self-organized mob: no navigator

| PRACTICE | DO | DON'T | |

| Mob | Listen, discuss goals, communicate intent and instruct the DRIVER |

Make suggestions, express support or disagreement or ask questions any time Establish consensus or consent (no disagreement) Tell DRIVER what to try at the level they are able to execute |

Talk over one another |

| Driver | Listen, implement ideas coming from the MOB, ask for clarification or technical help |

Ask the MOB for clarification Offer ideas to the MOB when needed |

Type anything before being instructed by the MOB |

First impressions

Come 5 o’clock I felt... Exhilarated! And also, incredibly exhausted. This retreat was one heck of a ride.

It’s safe to assume that everyone who participated is essentially a developer, which means we spend our workdays working from home, sitting in front of a screen. If these folks decide to spend their Saturday sitting in front of a screen to try something new, that’s a massive level of dedication. That’s a great premise to start from, and it guarantees, at the very least, that this day is going to produce lots of new insight.

Also, workshops like this tend to cost a ton of money, and here the organizers were giving it away for free.

What struck me (and I’m being provocative here) is how little each group got done after having four or five smart people work on a toy exercise for a full day. We all had a handful of tests for an average of one tiny class, which was typically saddled with a deep conceptual misunderstanding. Individually, each of us could have solved the task at hand two or three times over in the same time.

To which it’s fair to point out, as people did in the closing all-hands retrospective, that each team actually achieved a lot, if we just look at it from the right angle:

- We had to juggle a novel and complex tech setup involving Zoom, the online timer and the online code editor.

- We also had to understand, internalize and perform the new and unusual theater of the mob programming roles and styles.

- There was a lot of diversity in programming experience, knowledge of the chosen programming language, and English proficiency. Heck, when was the last time you were giving or receiving micro-editing instructions about indenting code, opening parentheses, closing curly brackets and the like?

- In spite of all this, the teams actually ended up with a shared understanding of the problem and the seed of a potential solution.

It is very hard to carry on a coherent line of thought over two or more role-switches and get something done over a longer arc. A few times this flow happened during the day, and when it did, the endorphine kick was massive.

I would be totally up to trying this out this over more than just a single day.

The million dollar question: Isn’t this super inefficient?

Before lunch break a minor controversy emerged around test-driven development, with the predictable extremes of “I never write tests and I don’t see the point” and “Code without tests is not even code, it’s just scribbles on a napkin.” The hosts quickly and decisively steered the crowd away from that fruitless debate, which left the room open for the other nagging question: But... is this even feasible? How is this efficient? Isn’t it just a waste of five people’s time?

That’s a great question, and I’d love to know the answer.

Mob programming lives under the broader agile umbrella, and contrary to popular belief, the point of agile is to make teams slower, not faster. A big part of agile discipline is to limit the amount of work items on the board, and to timebox efforts into two or three-week sprints. Before, we had scope creep, missed deadlines, recurring conflicts between stakeholders, unpredictability, pressure, and burnout. Agile’s promise is to have less of all that.

Every kind of knowledge work is fiercely hard to scale beyond one brain, and most methodologies are essentially modern implementations of the (supposedly African) proverb, If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together.

If that’s the goal, I can see how mob programming might deliver. Its main promise, after all, is to improve the bus factor in organizations, i.e., the minimum number of people whose disappearance (by way of getting hit by a bus) would kill the project because of the knowledge/skills/competence they, and only they, possess. It’s about never having irreplaceable people.

While that sounds intuitively right, there are other promises where I am sitting on the fence. Does the wisdom of the crowd lead to better solutions and better quality? Or does it mean that teams settle on the lowest common denominator? Are mobs ultimately faster because their joint wisdom avoids pitfalls, or does the overhead end up making them less efficient than asynchronous forms of collaboration?

It appears that there aren’t any compelling, evidence-based answers to these questions in the literature. That is in itself a fascinating fact, but I’ll have to leave that for another time.[8]

Other takeaways

The day brought a couple of highlights for me that are not strictly about mob programming.

Tooling matters. No, seriously, tooling matters. The setup with screen sharing, the online timer and cyber-dojo was incredibly efficient, and yet even this way, every handover took at least 30 seconds. Half a minute out of every 4 minutes is a non-negligible overhead. People who have done this in real-life remote settings said they had used a Git commit/push/pull workflow, which was even more overhead, forcing them to extend the cycle to up to 15 minutes.

With the right tooling, this works, if only barely. Without the right tooling, it’s unimaginable.

The lack of a proper IDE was another striking experience. IntelliSense, auto-formatting, refactoring tools like Rename, Find references, Go to definition, powerful editing features like block insertion, syntax highlighting – creature comforts like these represent several multiples of developer productivity. Cyber-dojo is an amazing browser-based tool, but in comparison to a proper IDE, working in it felt genuinely crippling. Oh, did I mention the lack of debugging?

Language also matters. I mean human language: if you’re in a collaborative setting that focuses 100% on verbal communication, using a language where someone is not entirely fluent is a real obstacle. You need to keep this in mind if you’re thinking of trying mob programming in a real-life situation. It limits your options with regards to team composition.

It felt not entirely right to have an event without a clear, explicit commitment to inclusivity and a code of conduct. The Berlin Code of Conduct[9] could be a readily availably option that’s already worked out and well established; it is used by various other meetups. Four out of the twenty-plus participants were women, and their voice was almost entirely suppressed by three or four loud men in the shared discussions. Moderation is a tough activity and the hosts did their best, but more emphasis would be useful in future events.

The introvert factor

There’s a psychological angle that’s been with me ever since the retreat, and for me it’s perhaps the biggest question mark about mob programming. Obviously I’m thinking about this because I’m a typical member of the introvert tribe myself.

Compared to the general population, an outsized proportion of programmers are introverts. Is it a case that programming just happened to be populated by folks like this, and so it’s become an introverts’ field? Or is there something about programming as an activity that by its nature attracts a type of personality? However that may be, a lot of the talent in software are just introverts.

If you’re an introvert that means you recharge when you are alone, and your energy is drained when you are in interaction with others. Mob programming? 100% interaction. Just as I wrote, it was a thrilling day, but for me, it was also incredibly exhausting. I could do this for a week, maybe for a stretch of two weeks, but I cannot permanently exist with this level of people interaction.

In other words, my main doubt is: aside from occasional timeboxed settings, can a methodology like mob programming that is 100% interaction be a good match for a population with an exceptionally high need for solitude? Would we be doing ourselves a favor by putting our charmingly introverted programmers in a setting that’s permanently draining for them?

The race to find the ideal way to make teams slower is still on.

References

[1] meetup.com/Software-Craftsmanship-Berlin/events/276256303/

[2] twitter.com/dimitrypolivaev

[4] Available at a shared Google Docs link; © 2020 Dimitry Polivaev, Bob Allen, licensed CC-BY.

[6] cyber-dojo.org/creator/home

[8] A reader of my first draft has pointed out that Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps by Nicole Forsgren et al. [publisher] marshals evidence that shorter release cycle times predict the success of companies. That fact has some bearing on my question, since methods like pair programming tend to eliminate delays that result from asynchronous work.