Neural MT: hip young technology looking for a business model

Hello! I am Neural M. Translation. I’m new around here. I am intelligent, witty, sometimes wildly funny, and I’m mostly reliable. My experiences so far have been mixed, but I haven’t given up on finding a business model for lifelong love.

That’s the sort of thing that came to my mind when I read the reports about DeepL Translator[1], the latest contender in the bustling neural MT space. The quality is impressive and the packaging is appealing, but is all the glittering stuff really gold? And how will the company make money with it all? Where’s the business in MT, anyway?

I don’t have an answer to any of these questions. I invite you to think together.

Update: I already finished writing this post when I found this talk (in German) by Gereon Frahling, the sparkling mind behind Linguee, from May 2017. It contains the best intro to neural networks I’ve ever heard, and sheds more light on all the thinking and speculation here. I decided not to change my text, but let you draw your own conclusions instead.

Scratching the DeepL surface

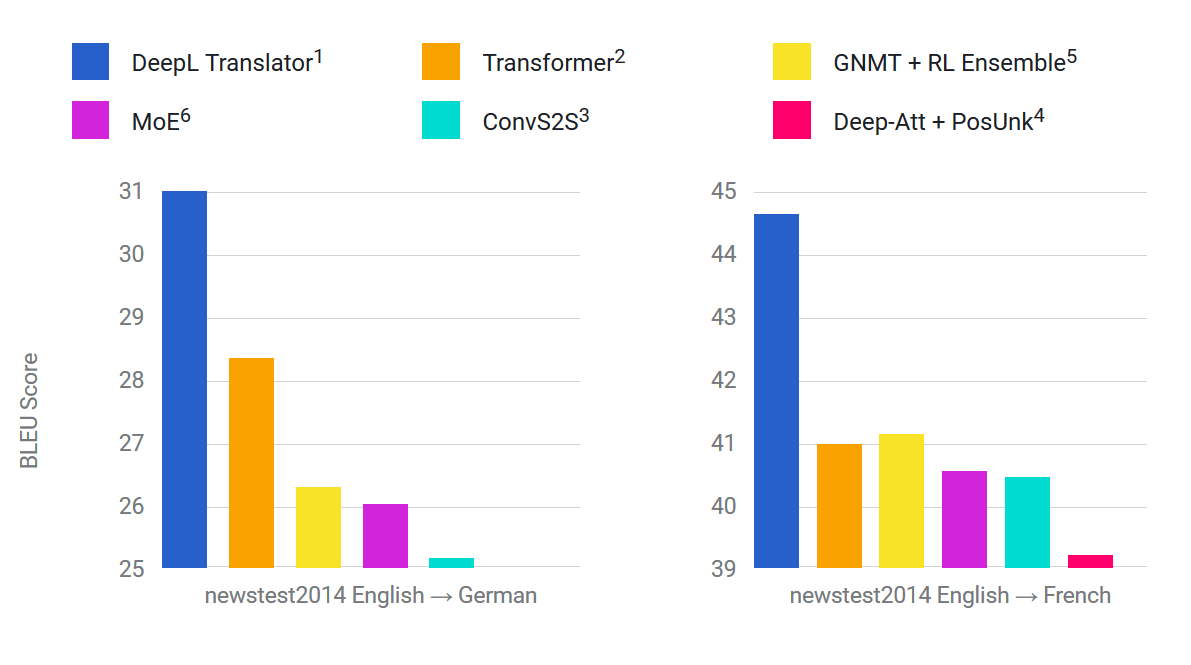

If you’ve never heard of DeepL before, that’s normal: the company changed its name from Linguee on August 24, just a few days before launching the online translator. The website[2] doesn’t exactly flood you with information beyond the live demo, but the little that is there tells an interesting story. First up are the charts with the system’s BLEU scores:

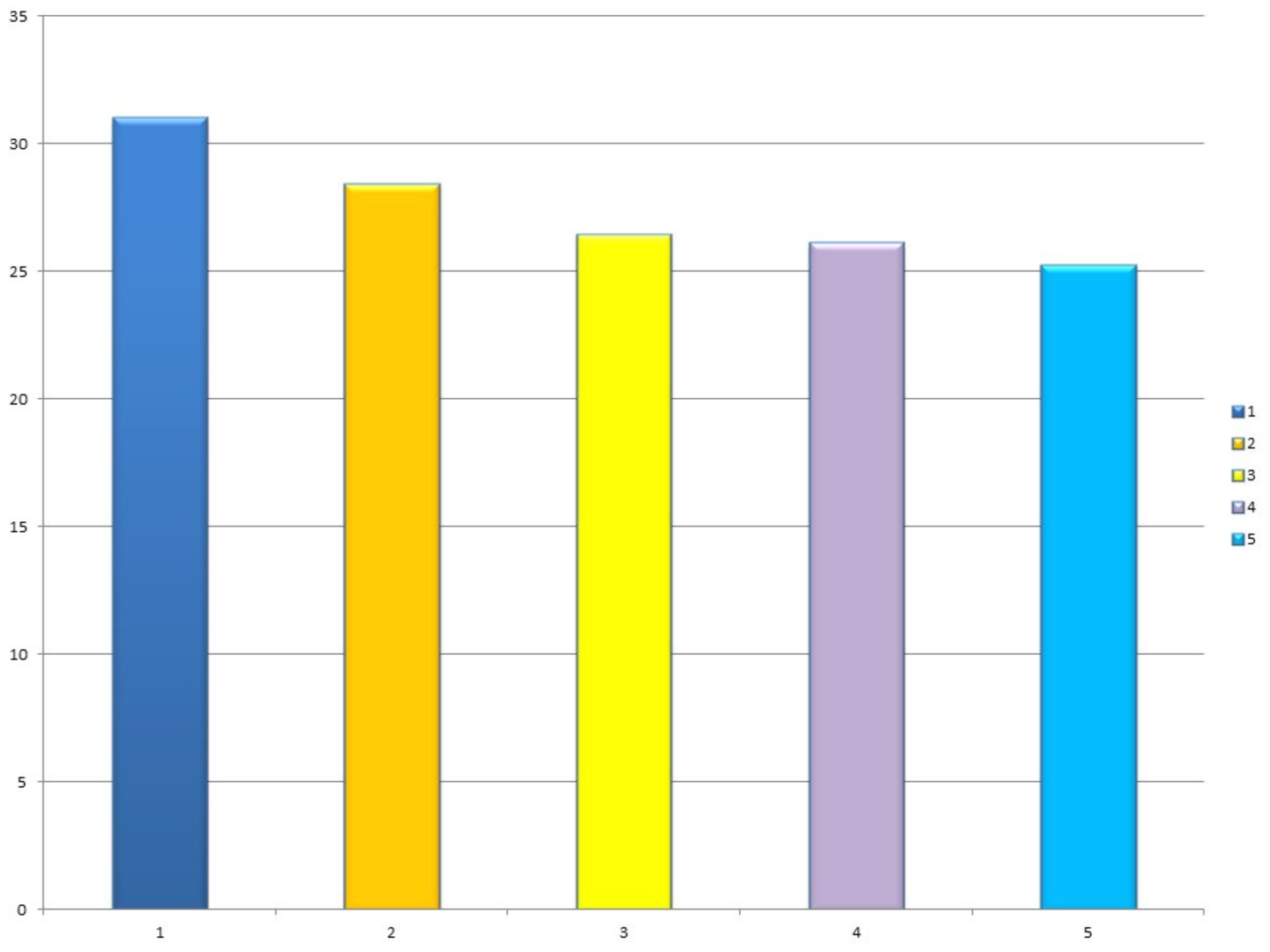

I’ll spare you the bickering about truncated Y axes and just show what the full diagram on the left looks like:

This section seems to be aimed at folks who know a bit about the MT field. There are numbers (!) and references to research papers (!), but the effect is immediately destroyed because DeepL’s creators have chosen not to pubish their own work. All you get is the terse sentence, Specific details of our network architecture will not be published at this time. So while my subjective judgement confirms that the English/German translator is mighty good, I wonder why the manipulation is needed if your product really speaks for itself. Whence the insecurity?

Unfortunately, it gets worse when the text begins to boast about the datacenter in Iceland. What do these huge numbers even mean?

My petaFLOPS are bigger than your petaFLOPS

The neural in NMT refers to neural networks, an approach to solving computationally complex tasks that’s been around for decades. It involves lots and lots of floating-point calculations: adding and multiplying fractional numbers. Large-scale computations of this sort have become affordable only in the last few years, thanks to a completely different market: high-end graphics cards, aka GPUs. All those incredibly realistic-looking monsters you shoot down in video games are made up of millions of tiny triangles on the screen, and the GPU calculates the right form and color of each of them to account for shape, texture, light and shadow. It’s an amusing coincidence that these are just the sort of calculations needed to train and run neural networks, and that the massive games industry has been a driver of GPU innovation.

One TFLOPS or teraFLOPS simply means the hardware can do 1,000 billion floating-point calculations per second. 5.1 petaFLOPS equals 5,100 TFLOPS. NVIDIA’s current high-end GPU, the GTX 1080 Ti, can do 11 TFLOPS.

How would I build a 5.1 PFLOPS supercomputer? I would take lots of perfectly normal PCs and put 8 GPUs in each: that’s 88 TFLOPS per PC. To get to 5.1 PFLOPS, I’d need 58 PCs like that. One such GPU costs around €1,000, so I’d spend €464k there; plus the PCs, some other hardware to network them and the like, and the supercomputer costs between €600k and €700k.

The stated reason for going to Iceland is the price of electricity, which makes some sense. In Germany, 1kWh easily costs up to €0.350 for households; in Iceland, it’s €0.055[3]. Germany finances its Energiewende largely by overcharging households, so as a business you’re likely to get a better price, but Iceland will still be 3 to 6 times cheaper.

A PC with 8 GPUs might use 1500kW when fully loaded. Assuming they run at 50% capacity on average, and 8760 hours in a year, the annual electricity bill for the whole datacenter will be about €21k in Iceland.

But is this really the world’s 23rd largest supercomputer, as the link to the Top 500 list[4] claims? If you look at the TFLOPS values, it sounds about right. But there’s a catch. TFLOPS has been used to compare CPUs, which can do lots of interesting things, but floating-point calculations are not exactly their forte. A GPU, in turn, is an army of clones: it has thousands of units that can do the exact same calculation in parallel, but only a single type of calculation at a time. Like calculating one million tiny triangles in one go; or one million neurons in one go. Comparing CPU-heavy supercomputers with a farm of GPUs is like comparing blackberries to coconuts. They’re both fruits and round, but the similarity ends there.

Business model: free (or cheap) commodity MT

There are several signs suggesting that DeepL intends to sell MT as a commodity to millions of end users. The exaggerated, semi-scientific and semi-technical messages support this. The highly professional and successful PR campaign for the launch is another sign. Also, the testimonials on the website come from la Reppublica (Italy), RTL Z (Holland), TechCrunch (USA), Le Monde (France) and the like – all high-profile outlets for general audiences.

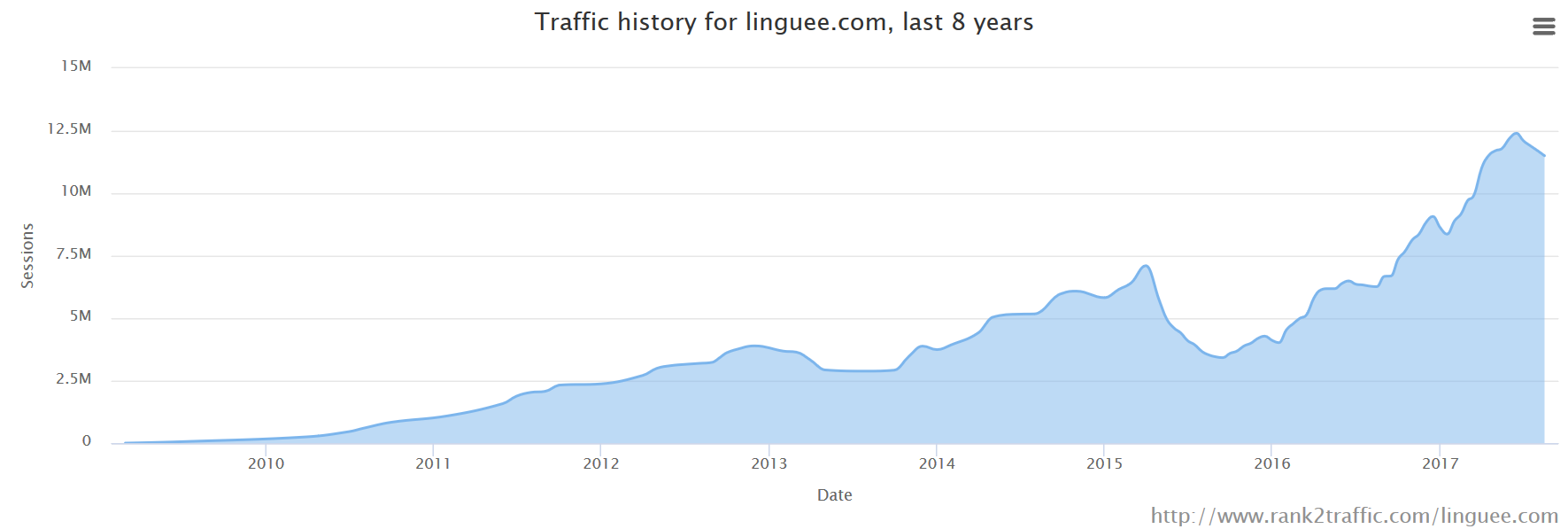

Right now there is only one way to make money from mass content on the Internet: ads. And that in fact seems to have been the company’s model so far. Here’s Linguee’s traffic history from Alexa:

With 11.5 million monthly sessions, almost 3 pageviews per session, and a global rank of around 2,500, linguee.com is a pretty valuable site. Two online calculators place the domain’s value at $115k and $510k.[5][6]

If you assume an average ad revenue[7] of $1 per thousand impressions (PTM), that would yield a monthly ad revenue of $34,500. This kind of mileage, however, varies greatly, and it may be several times higher, especially if the ads are well targeted. Which they may (or may not) be on a site where people go to search in a sort of dictionary.

Let’s take a generous $3 PTM. That yields an annual revenue of $1.2mln, which I’ll just pretend is the same in euros. Assuming a 3-year depreciation for the initial datacenter investment and adding the energy cost, you’d need an extra traffic of about 2 million sessions to break even, ignoring wages and development costs. That could be achievable, I guess.

Why commodity MT is a bad idea nonetheless

What speaks against this approach? Let’s play devil’s advocate.

Barrier to switch. It’s hard to make people switch from a brand (Google) that is so strong it’s become a generic term like Kleenex. Is the current quality edge enough? Can you spin a strong enough David-versus-Goliath narrative? Raise enough FUD about privacy? Get away with a limited set of languages?

Too big a gamble. Public records show that Linguee/DeepL had a €2.4mln balance sheet in 2015, up from €1.2 the year before. Revenue numbers are not available, but the figures are roughly in line with the ballpark ad income that we just calculated. From this base, is it a sensible move to blow €700k on a top-notch datacenter, before your product even gains traction? Either the real business model is different, or the story about the datacenter is not completely accurate. Otherwise, this may be a rash step to take.

Unsustainable edge. Even if you have an edge now, and you have a dozen really smart people, and you convince end users to move to your service and click on your ads, and your investment starts to pay off, can you compete with Google’s generic MT in the long run?

I think you definitely cannot. Instead of explaining this right away, let’s take a closer look at the elephant in the room.

Google in the MT space

First, the humbling facts. From a 2016 paper[8] we can indirectly get some interesting figures about Google’s neural MT technology. One thing that stands out is the team size: there are 5 main authors, and a further 26 contributors.

Then there’s the training corpus: for a major language pair such as English/French, it’s between 3.5 billion and 35 billion sentence pairs. That’s 100-1000 times larger than the datasets used to train the state-of-the-art systems at the annual WMT challenge.[9] Systran’s 2016 paper[10] reports datasets ranging from 1 million to over 10 million segments, but billions are nowhere to be found in the text.

In this one respect, DeepL may be the single company that can compete with Google. After all, they spent the past 8 years crawling, classifying and cleansing bilingual content from the web.

Next, there is pure engineering: the ability to optimize these systems and make them work at scale, both to cope with billion-segment datasets and to serve thousands of request per second. A small company can make a heroic effort to create a comparable system right now, but it cannot be competitive with Google over several years. And every company in the language industry is homeopathically small in this comparison.

Third, there is hardware. Google recently announced its custom-developed TPU,[11] which is basically a GPU on steroids. Compared to the 11 TFLOPS you get out of the top-notch GTX 1080 Ti, a single TPU delivers 180 TFLOPS.[12] It’s not for sale, but Google is giving away 1000 of these in the cloud for researchers to use for free. Your datacenter in Iceland might be competitive today, but it will not be in 1, 2 or 3 years.

Fourth, there is research. Surprisingly, Google’s MT team is very transparent about their work. They publish their architecture and results in papers, and they helpfully include a link to an open-source repository[13] containing the code and a tutorial. You can grab it and do it yourself, using whatever hardware and data you can get your hands on. So, you can be very smart and build a better system now, but you cannot out-research Google over 1, 2 or 3 years. This is why DeepL’s hush-hush approach to technology is particularly odd.

But what’s in it for Google?

It’s an almost universal misunderstanding that Google is in the translation business with its MT offering. It is not. Google trades in personal information about its real products: you and me. It monetizes it by selling to its customers, the advertisers, through a superior ad targeting and brokering solution. This works to the extent that people and markets move online, so Google invests in growing internet penetration and end user engagement. Browsers suck? No problem, we build one. There are no telephone cables? No problem, we send balloons. People don’t spend enough time online because they don’t find enough content in their language? No problem, we give them Google Translate.

If Google wants to squash something, it gets squashed.[14] If they don’t, and even do the opposite by sharing knowledge and access freely, that means they don’t see themselves competing in that area, but consider it instead as promoting good old internet pentration.

Sometimes Google’s generosity washes over what used to be an entire industry full of businesses. That’s what happened to maps. As a commodity, maps are gone. Cartography is now a niche market for governments, military, GPS system developers and nature-loving hikers. The rest of us just flip open our phones; mass-market map publishers are out of the game.

That is precisely your future if you are striving to offer generic MT.

Business model: professional translation

If it’s not mass-market generic translation, then let’s look closer to home: right here at the language industry. Granted, there are still many cute little businesses around that email attachments back and forth and keep their terminology in Excel sheets. But generally, MT post-editing has become a well-known and accepted tool in the toolset of LSPs, next to workflow automation, QA, online collaboration and the rest. Even a number of adventurous translators embrace MT as one way to be more productive.

The business landscape is still pretty much in flux, however. We see some use of low-priced generic MT via CAT tool plugins. We see MT companies offering customized MT that is more expensive, but still priced on a per-word, throughput basis. We see MT companies charging per customized engine, or selling solutions that involve consultancy. We see MT companies selling high-ticket solutions to corporations at the $50k+ level where the bulk of the cost is customer acquisition (golf club memberships, attending the right parties, completing 100-page RFPs etc.). We see LSPs developing more or less half-baked solutions on their own. We see LSPs acquiring professional MT outfits to bring competence in-house. We even see one-man-shows run by a single very competent man or woman, selling to adventurous translators. (Hello, Terence! Hello, Tom!)

There are some indications that DeepL might be considering this route. The copy on the teaser site talks about translators, and the live demo itself is a refreshingly original approach that points towards interactive MT. You can override the initial translation at every word, and if you choose a different alternative, the rest of the sentence miraculously updates to complete the translation down a new path.

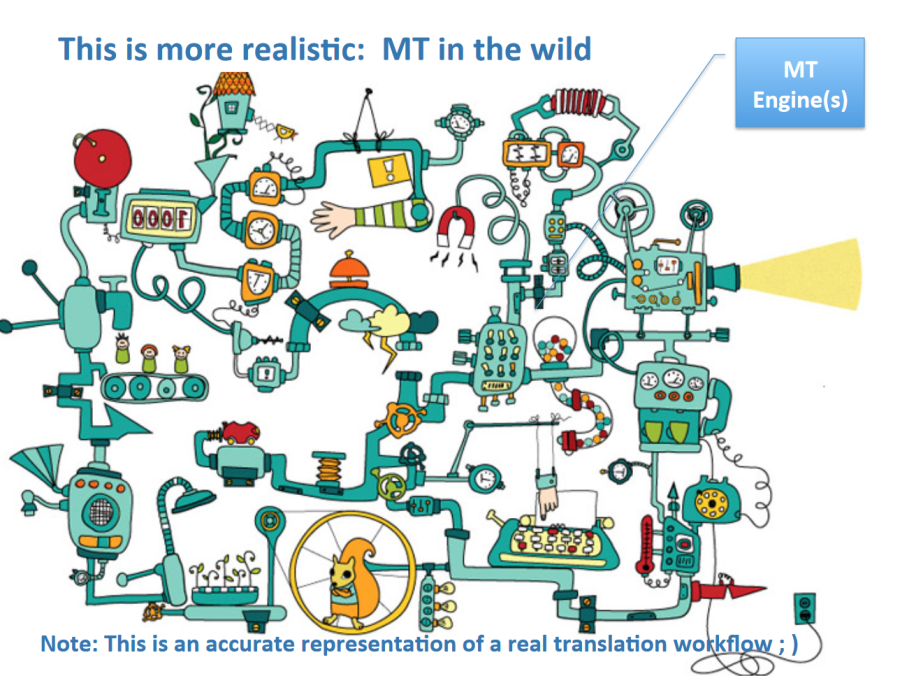

The difficulty with this model is that translation/localization is a complex space in terms of processes, tools, workflows, and interacting systems. Mike Dillinger showed this slide in his memoQfest 2017 keynote[15] to illustrate how researchers tend to think about MT:

He immediately followed it up with this other slide that shows how MT fits into a real-life translation workflow:

Where does this leave you, the enthusastic MT startup that wants to sell to the language industry? It’s doable, but it’s a lot of work that has nothing to do with the thing you truly enjoy doing (machine translation). You need to learn about workflows and formats and systems; you need to educate and evangelize; you need to build countless integrations that are boring and break all the time. And you already have a shark tank full of competitors. Those of us who are in it think the party is good, but it’s not the kind of party where startup types tend to turn up.

What does that mean in numbers? I looked at the latest available figures of Systran.[16] They are from 2013, before the company was de-listed from the stock exchange. Their revenue then was $14.76mln, with a very flatly rising trend over the preceding two years. If your current revenue is around €2mln, that’s a desirable target, but remember that Systran is the company selling high-ticket solutions through a sales force that stays in expensive hotels and hangs out with politicians and CEOs. That sort of business is not an obvious match for a small, young and hungry internet startup.

Business model: commercial lubricant

By far the most interesting scenario, for me at least, is what companies like eBay or Booking.com are doing. They are not in the translation business, and they both have internal MT departments.[17][18] The funny thing is, they are not MTing their own content. Both companies are transaction brokers, and they translate the content of their customers in order to expand their outreach to potential buyers. With eBay it’s the product descriptions on their e-commerce site; with Booking.com, it’s the property descriptions.

For these companies, MT is not about “translation” in the traditional sense. MT is a commercial lubricant.

The obvious e-commerce suspect, Amazon, has also just decided to hop on the MT train.[19] The only surprising thing about that move is that it’s come so late. The fact that they also intend to offer it as an API in AWS is true Amazon form; that’s how AWS itself got started, as a way to monetize idle capacity when it’s not Black Friday o’clock.

So we’ve covered eBay, Booking.com and Amazon. Let’s skip over the few dozen other companies with their own MT that I’m too ignorant to know. What about the thousands of smaller companies for whom MT would make sense as well, but that are not big enough to make it profitable to cook their own stew?

That’s precisely where an interesting market may be waiting for smart MT companies like DeepL.

Speed dating epilogue

Will Neural M. Translation, the latest user to join TranslateCupid, find their ideal match in an attractive business model? The jury is still out.

If I’m DeepL, I can go for commoditized generic MT, but at this party, I feel like a German Shepherd that accidentally jumped into the wrong pool, one patrolled by a loan shark. It feels so wrong that I even get my metaphors all mixed up when I talk about it.

I can knock on the door of translation companies, but they mostly don’t understand what I’m talking about in my pitch, and many of them already have a vacuum cleaner anyway, thank you very much.

Maybe I’ll check out a few interesting businesses downtown that are big enough so they can afford me, but not so big that the goons at the reception won’t even let me say Hi.

Will it be something completely different? I am very excited to see which way DeepL goes, once they actually reveal their plans. Nobody has figured out a truly appealing business model for MT yet, but I know few other companies that have proven to be as smart and innovative in language technology as Linguee/DeepL. I hope to be surprised.

Should we brace for the language industry’s imminent “disruption?” If I weren’t so annoyed by this brainlessly repeated question, I would simply find it ridiculous. Translation is a $40bln industry globally. Let’s not talk about disruption at the $1mln or even $100mln level. Get back to me when you see the first business model that passes $1bln in revenues with a robust hockey-stick curve.

Or, maybe not. If machine learning enables a new breed of lifestyle companies with a million bucks of profit a year for a handful of owners, I’m absolutely cool with that.

References

[3] en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electricity_pricing

[4] www.top500.org/list/2017/06/

[6] www.estibot.com/appraise.php

[7] www.quora.com/How-much-does-a-website-with-AdSense-earn-on-average-per-100-000-impressions

[9] www.statmt.org/wmt17/translation-task.html

[11] cloud.google.com/blog/big-data/2017/05/an-in-depth-look-at-googles-first-tensor-processing-unit-tpu

[12] www.theinquirer.net/inquirer/news/3010365/google-announces-tpu-20-with-180-teraflop-max-out-for-ai-acceleration

[13] github.com/tensorflow/tensor2tensor#walkthrough

[14] gizmodo.com/yes-google-uses-its-power-to-quash-ideas-it-doesn-t-li-1798646437

[15] www.memoq.com/Kilgray/media/memoQfest/memoQfest2017/Presentations/Hybrid-intelligence-translation-forging-a-real-partnership-between-humans-and-machines.pdf

[16] www.hoovers.com/company-information/cs/revenue-financial.systran_sa.69b0b68eaf2bf14f.html

[17] slator.com/features/inside-ebay-translation-machine/

[18] slator.com/technology/booking-com-builds-harvard-framework-run-neural-mt-scale/

[19] slator.com/technology/whats-amazon-up-to-in-machine-translation/